golden train

Golden Train

Part of a series of 3 connected works for the ‘Stay’ Exhibition at The Great Eastern Hotel, Liverpool Street, London. – A site-specific work, linking the Hotel’s Historical and current use.

An image showing the projected film installation ‘Eternity 2’ on to the connecting staircase leading to ‘Golden Train’.

Review of Eternity and Golden Train installations at Great Eastern Hotel, Summer 2005,

by Cherry Smyth

Mark Dixon is fascinated by the intersection of people and places in the present and diachronically. He’s drawn to ghostly or unearthly presences, whether it’s filaments of static flashing between two charged points, or the absence of a local railway track that once linked village to town to city in East Anglia. Like a railway system, he likes to connect disparate sites and create that spark of knowing-you’re-thinking, when a fresh mental connection makes a new pathway for our brain’s neurons.

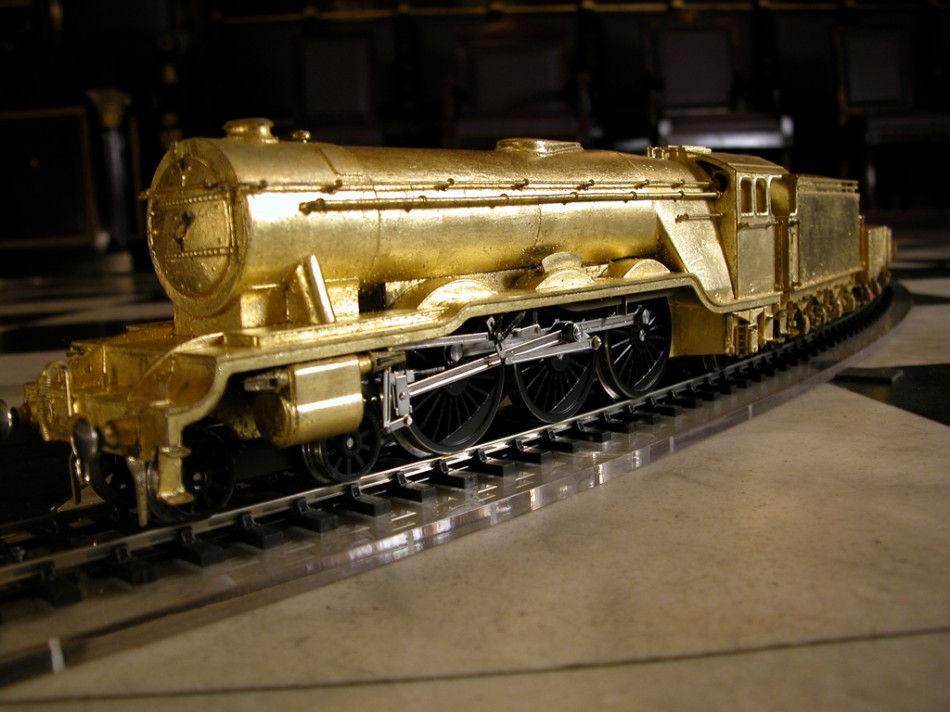

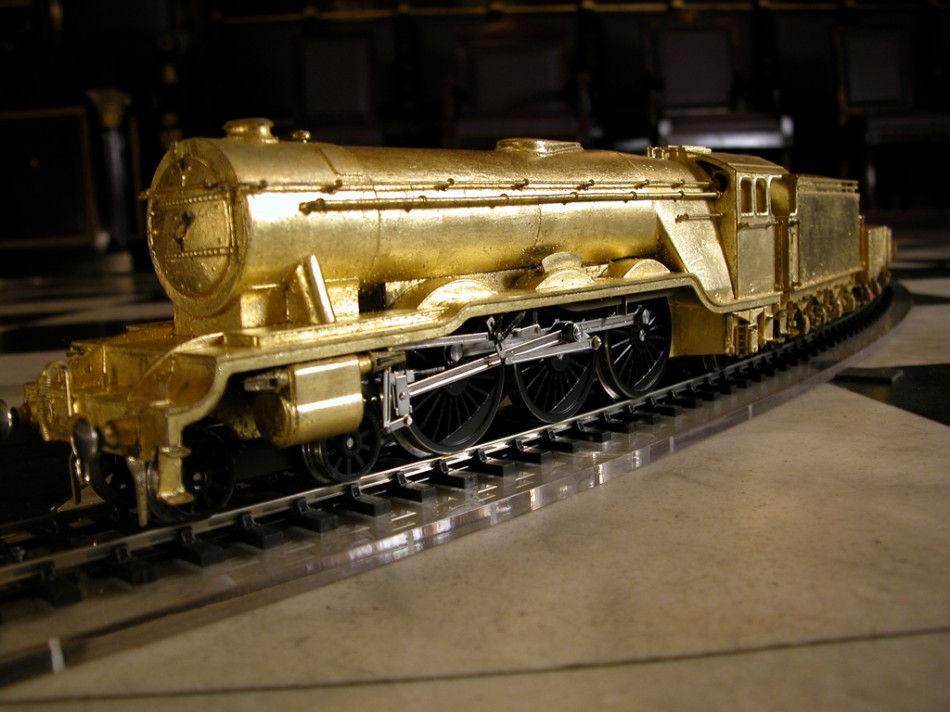

His three-part installation at the Great Eastern Hotel synthesized and developed his practice, using a range of media across three sites. Onto the wall of the grand marble staircase that leads up from the exclusive Fishmarket restaurant to the function rooms, Dixon projected ‘Eternity 1’, a DVD loop that filled the entire wall and gave the illusion of another space. Close up footage of a scale model of an ‘O’ gauge steam train, covered in goldleaf, circling on a track, dissolves to slow-motion shots of glasses being dipped into a silver bucket of water and polished by hand. The lushness of golden light and dappled water reflects the opulence of the surroundings and evokes the goldrush trains that took dreamers to California in the 19th century, and those chasing a dream of wealth in the hotel today, which largely serves City business. Money changes hands over glasses used to lubricate and clinch a deal. The circularity of the motion of the train and the cloth polishing the glass, suggests the repetitiveness of the routines not only of the commuters who frequent the hotel, but also of the staff working behind the scenes.

As the hotel sits directly above Liverpool Street Station, the piece also invokes the railway and tube workers and the intricate webbing of journeys occurring behind the wall. As a grand Victorian Railway hotel, built in 1884 and extended in 1901, the Great Eastern depended on these journeys for its location and function. By 1914, the rail system had reached its peak in geographic coverage of Britain.

‘Eternity 1’ is a dreamy, evocative work that acts as a trailer for Dixon’s following two installations.

‘Eternity 2’ is another short video loop projected onto the pale green carpet of the stairs, connecting a corridor, past the entrance to the kitchen, to the Masonic Temple. When the artists were given a tour of the hotel in January 2005, to select sites for their work, they had to step around a group of staff polishing glasses and cutlery in the corridor and on the staircase. In Dixon’s video, a circle of six employees sits on the stairs, dipping and polishing the same six glasses, which are passed from one to the other in an endless loop. Again Dixon explores hierarchies of labour – how the comfort and leisure of hotel guests depends on the unseen labour of these mostly Polish polishers. By slightly slowing the speed of the footage, Dixon encourages your gaze to linger and makes the scene more languid and strange. The visual tones are stunning. The dark staff uniforms merge with the dark wood paneling of the staircase, so that their pale faces and white serviettes take on an uncanny spectral quality, summoning not only absent contemporary staff, but also the century of staff who’ve run the hotel since it first opened in 1884.The chiaroscuro and the composition lend the mood of a domestic interior by a Dutch master. The decision to play the piece without sound also emphasises its painterly quality and evokes centuries of art history and another kind of labour of which Dixon is a worthy heir. By re-enacting the staff’s daily rituals, Dixon gives their work attention and dignity. As poet Thomas A. Clark wrote: ‘The routines we accept can strangle us but the rituals we choose give renewed life.’ (1)

Visitors to the showcase, who had to step on ‘Eternity 2’ to proceed to the next part of the installation, were reluctant to ‘hurt’ the staff or disrupt the beauty and integrity of the projected image. Through this physical interaction, the spectator became more engaged in the work, as in a theatrical, live piece and experienced the invisible hierarchy more acutely by climbing the steps and ‘trampling’ on the ’employees’.

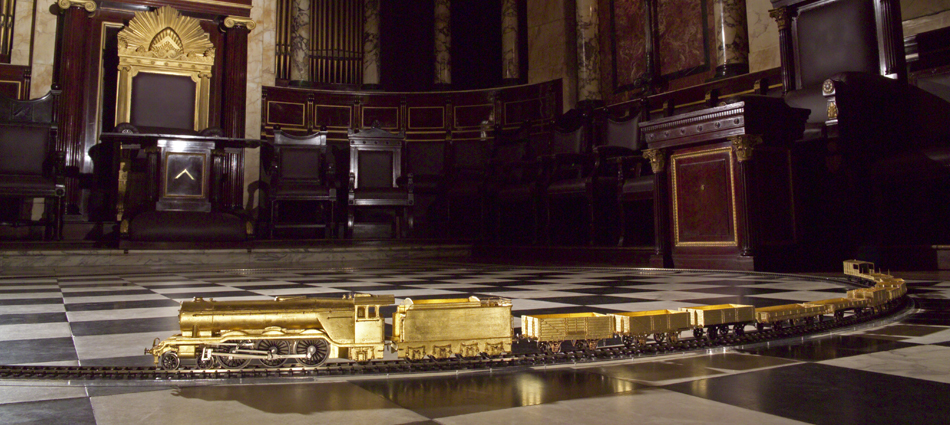

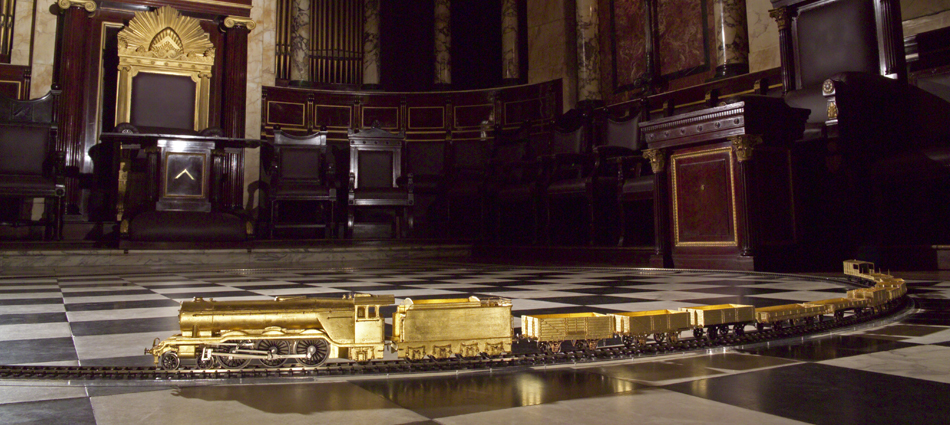

Dixon’s third piece, ‘Golden Train’, was installed in the magnificent splendour of the Masonic Temple, hidden in the depths of the hotel. A small golden model train chases its tail on a circular track that perfectly echoes the circular dome of the ceiling, its twelve wagons echoing the twelve Zodiac signs in gold relief on its surface. With the throne-like chairs and rich cararra marble columns and walls, the golden train, so sought after in ‘Eternity 1’, is reduced to the toy train of an absent despot, the only sound being its wheels clicking forlornly on the track. Again Dixon makes a myriad of connections between the flow of capital and the flow of people on the railways. Railways brought capital to the cities and standardised time across the country. Freemasons, once skilled workers in stone, moved from place to place to work on any great building and invented a system of secret signs and passwords to identify each other. The Masons helped to fund and build the Great Eastern Hotel and the wealth of encoded emblems and iconography in the Temple adds poignancy to the diminutive train, carrying no people, its only cargo, a superficial gold.

Dixon’s three interlinking pieces create a layered pathway through culture and a unique itinerary through the history of the hotel and the journeys money and power make. The pieces work both as physical representations in the present, and also symbolically across time, delivering a rich, textured understanding of the significance of place, people and labour.

(1) Thomas A. Clark, ‘Distance and Proximity’, Pocketbooks, 2000

February 11, 2013 | Filed under Commissions and tagged with commission, installation, performative, train.

Tags: commission, installation, performative, train